Friday 28 September 2012

Buddy HOLLY and The CRICKETS: 20 Golden Greats

(#197: 25 March 1978, 3 weeks)

Track listing: That’ll Be The Day/Peggy Sue/Words Of Love/Every Day (sic)/Not Fade Away/Oh Boy/Maybe Baby/Listen To Me/Heart Beat (sic)/Think It Over/It Doesn’t Matter Any More (sic)/It’s So Easy/Well….All Right/Rave On/Raining In My Heart/True Love Ways/Peggy Sue Got Married/Bo Diddley/Brown Eyed Handsome Man/Wishing

Although I am not the world’s greatest fan of The X-Factor, I must admit that the early auditions are, I find, the most enjoyable part of each series. By that I don’t mean the built-in freak show elements – let’s find some hapless no-hopers to laugh at with an air of unearned superiority – but the point when genuine contenders are raw and relatively unformed, before being hauled off into the boring and aptly titled “boot camp” episodes, where every atom of individuality and original thought is surgically excised in the outdated hope that the new Mariah or Bublé will magically emerge.

Somewhere in between those two extremes was the elderly chap – I think his name was Nick – who turned up on the show a couple of episodes ago. He said he had won numerous talent contests over the year, although did not yield locations or dates. He proceeded to perform and it was quickly clear that he wasn’t going to get through; his bodily rhythm did not quite work in tandem with his voice, which in turn wasn’t in complete synchronisation with the song’s melody or beat. Nevertheless, it was heartfelt, and the song he was singing was “Maybe Baby,” a song not written by Buddy Holly, but by Glen D Hardin and Norman Petty (although there are some whispers that Holly’s mother may have contributed the original lyrics). Apart from the eximious Louis Walsh, who voted to keep him on the show, the rest of the judges were aghast and dismissive. Nick roared that they knew nothing, that the whole show was based on lies, and stormed off.

I’m not sure that he was wrong. It did help that “Maybe Baby” was one of the few songs on the show which was more than two years old – and that, along with “Let’s Get It On” (come on, Nathan!), it was memorable in ways that other songs “soulfully” hollered weren’t – but Nick’s performance I found remarkable, insofar as it clearly connected with something, a passion, a glimmer, he had felt in the distant past and perhaps still did; that he was there when this music was new and therefore understood it, knew his way around it, in ways that those who came after him could not hope to know or understand. And also that he understood more about the instinctive magic at the heart of so much of the best pop music than those planning to become Young Business Entertainer Of The Year.

Speaking of instinct and magic naturally brings me back to Buddy Holly. Now, imagine if this were the kind of blog so many people tell me they want it to be, something a lot more “accessible” and a lot less “elitist” (and something which would probably get the blog a whole lot more hits than it gets at the moment). I’d have little option but to undertake a tedious chronological slog through Holly’s brief life and less brief legacy, going through his upbringing in Lubbock, his early interest in Tex-Mex and Western Swing, his Western and Bop band with Bob Montgomery, his initial, unsuccessful Nashville recordings for Decca, his eventual move to Clovis, New Mexico, the formation of the Crickets and his fateful meeting with Norman Petty which led to, as the sarcophagus-like capitalised sleevenote puts it: “9 TOP TEN SMASH HITS” (“IN JUST EIGHTEEN MONTHS”). Then there would be the split from the Crickets, the attempt by Petty to reposition him in a tamer teenpop market with Dick Jacobs’ orchestrations, his move to New York, his rapid courting of and marriage to Maria Elena Santiago, and finally the ‘plane crash and his many posthumous hits, leading to a brief discussion of his legacy, enormous enough to affect most who came after him in rock, from the Beatles on down, and further pondering on the unanswerable question of what might have happened, what he might have done, had he lived (at the time of his death he was just about learning the ways of record production, and indeed had already produced the young Waylon Jennings).

I’m not sure who would sustain the greater insult here; my readers, who such people assume are thick slowcoaches who need to be told everything, baby spoonfeeding style (“Why don’t you do a potted history of each artist rather than assuming that everyone automatically knows who or what you’re talking about?” as one such comment reads, as though brains or Google didn’t exist), or me, for the implication that my writing is otiose and impenetrable (“People these days have a short attention span – they don’t have time to sit down and read long thinkpieces about obscure old number one records nobody’s going to listen to anyway.” One wonders how folk back in Victorian times, without any of today’s technological conveniences to hand, managed to work their way through hundreds of pages of Thomas Carlyle or Henry Mayhew and still do a full, long day’s work, go for long walks and attend to household chores and perhaps also families). Well, I’m not here to patronise, and my assumption is that you are here reading this piece about Buddy Holly because you already know about his life and work and are interested to read what I have to say about him and his music, and in particular those aspects which don’t normally get talked about or which I have, rightly or wrongly, discerned from careful, attentive listening.

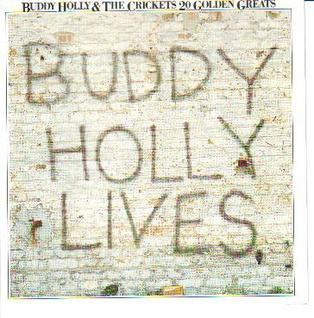

There were multiple factors at work with this particular 20 Golden Greats volume, apart from the usual TV advertising-generated nostalgia; in 1978 there was a movie, The Buddy Holly Story, with Gary Busey excellent in the title role, and there was also excitement stirred by Paul McCartney’s eventual purchase of Holly’s back catalogue publishing. There remained, in addition, a sense that the twenty tracks collected here, though only representing a small part of Holly’s amazingly prolific body of work, represented a kind of punk-inspired back to basics approach, a feeling aided by the small monochrome photograph on the rear cover showing Holly to bear a striking resemblance to the Elvis Costello of This Year’s Model. But there was also an expressly British tinge at work here; the cover graffiti, inscribed on the wall of a crumbling (and possibly condemned) building, with cracked plaster and exposed pipes clearly visible, related to an emotion more strongly felt in Britain than in the States, where Holly and the Crickets scored only two million sellers (“That’ll Be The Day” and “Peggy Sue”) and where Holly had no hits after “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” (in the USA, 20 Golden Greats made only #55 on Billboard; here it went triple platinum). In Britain, in contrast, a cult around Holly’s memory slowly built up (Joe Meek, who killed himself and his landlady on the eighth anniversary of Holly’s death, did this more assiduously than most) and the innumerable demos and studio tryouts Petty rescued and recut with New York session musicians continued to provide Holly with major hits right up until the advent of the Beatles. A twelve-track compilation, The Buddy Holly Story, charted soon after his death and stayed on the UK album chart for fully three years (it peaked at #2, behind the immovable South Pacific). So when the message reads “HE WAS AHEAD OF HIS TIME. HE DIED BEFORE HIS TIME. HIS MUSIC LIVES ON,” it was taken a lot more seriously in Britain.

Such devotion would mean little and baffle much if it weren’t for the continued instinctive power of the music of Holly and the Crickets. And yet, for all their instinct, songs like “That’ll Be The Day” and “Peggy Sue,” highly experimental though they are, sound as though the musicians playing them know exactly what they are doing. If one adjective were to be used to best address Holly’s overall demeanour on his hits, it would be “confident.” Even when trying out new ideas, new tempi, new approaches, there is something in Holly’s timbre and bearing which implies that he is never going to be at a loss. And if the relative brevity of these performances and Holly’s early passing suggest rock’s first petit maître, a peerless miniaturist, then it’s also fair to say that he and his players put every speck of attention and concentration on what they are doing, with exceptional attention to detail.

Take, for instance, “That’ll Be The Day,” one of the most insolently confident opening shots in rock ‘n’ roll that I can think of; not only does it formulate, for the first time, the classic self-reliant four-piece rock group lineup – lead and rhythm guitars, bass, drums and vocals, performing (largely) their leader’s own material (though Hardin and Petty contributed more than people think) – but as a song and performance, it dares you to turn away from it. Hidden behind his spectacles, Holly is less the genial geek and more a direct, raging forerunner of Costello; he is mocking his would-be departing lover, basically sneering that she doesn’t have the guts or will to walk out on him, and both Holly’s lead guitar and Jerry Allison’s AK47-like drumming presume – correctly – that she will want to stick around and see the rest.

Whereas “Peggy Sue” seems to have fallen to Earth from outer space, one of those page one pop records from seemingly nowhere which set the tone for everything that comes after it, like “Subterranean Homesick Blues” or “Magic Fly” or “Gangnam Style” (and doesn’t Psy, in his black shock of hair and tidy hornrims, resemble a slightly beefier K-Pop reincarnation of Holly?). I was struck by this after watching, at a young age, Holly and the Crickets performing the song on The Ed Sullivan Show; it is still disturbing viewing – where did these creatures land? Perhaps due to the lack of dimensional perspective afforded by fifties television cameras, Holly, at stage front, looks about twice the size and half the age of the Crickets behind him. With his partially-rimmed spectacles, he gives the impression of a newly-arrived Martian; there is something about the performance which is not quite “real.”

And yet the song is about finding a “love so rare and true.” That being said, Holly does almost nothing on the record to describe Peggy Sue; who she is, what she looks like. Yes, the song may originally have been called “Cindy Lou” before Allison suggested changing it to the name of his fiancée, but “Peggy Sue” here is little more than an abstract, a blank template for the listener to complete (“If you knew Peggy Sue”). Behind Holly’s voice are the murkiest, most thunderous drums you have ever heard (it sounds as though coming from the bottom of a well, and it was not surprising to see the beat returning less than a decade later as the foundation of “Paint It, Black”). Holly is in fact more interested in, and more spellbound by, the grain of those two words, “Peggy” and “Sue”; he rolls them round his tongue and larynx in every conceivable way, experimenting with, and being delighted by, the different effects each can cause, like a jazz musician snaking their way around a standard or a riff; he is clearly exulted by the new possibilities which now lie before him, and before long who or what Peggy Sue is, or might be, is superseded by the use of the name as a signifier without anything obvious being signified. In other words, “Peggy Sue” reminds me of another self-contained four-piece group at work in the same period, whose leader and main composer also came from Texas, and which cheerfully threw standard expectations of melody and rhythm out of the window, replacing them with their own new constructions and devices. Buddy Holly as rock ‘n’ roll’s Ornette Coleman? Not as farfetched as you might think; if there was ever such a thing as “free rock,” then “Peggy Sue” is its epitome, and maybe also its peak. But if “Peggy Sue” exhibits a childlike joy, then Holly’s final, and wholly unexpected, vocal swoop from high to low indicates that this is definitely the work of a grown man, ready to discover the wider world; Peggy Sue, in the meantime, becomes a sort of rock ‘n’ roll female equivalent of Stagger Lee, an abstract folk hero(ine) who can and will mean anything to everyone.

If these two songs are the clear high points of 20 Golden Greats, then the remainder of the songs (on side one, at least) show that Holly never stopped experimenting. With “Words Of Love,” he goes as far as to invent psychedelia ten years ahead of schedule, with its woozy, disorientated vocals and strange syllabic emphases (“feel-AH,” “real-AH,” “hear-AH,” “ear-AH”) which indicate an intoxication of awe. “Everyday” expresses patient expectation with ease, using little more than slapped knees and celeste as musical background; Holly’s onomatopoeic arch of anticipation on “ROLL-er-COAST-er” conveys his excitement very simply and effectively (as does his more subdued “Hey? A-hey-hey”). Rather than knee-slapping, the beat on “Not Fade Away” seems to be thrashed out on a cardboard box (see Lindsey Buckingham some two decades later) and Holly’s words now seem to defy reason as deftly as Dylan’s would soon do, missing out whole streams of syntax (“You know my love not fade away,” “Well love is real and not fade away”). His pent-up sexuality goes from child to man (“A-WAY”) and back again (“How I feel-EE!”). His guitar cuts in halfway like a battleship. By not quite “getting” Bo Diddley, he inadvertently invents something else.

If both “Everyday” and “Not Fade Away” show Holly is up for it, the immediate attack of “Oh Boy” confirms that he is also ready for it; now he growls and shrieks, and even the square backing vocals can’t deter the acidic entry of his guitar solo; at the end of the song, Allison lets off steam with an extended, post-coital cymbal hiss. You almost want to rush up to him and urge him to be more patient. “Heartbeat” had recently been desecrated by Showaddywaddy, its structural subtleties undermined by the crude rugby chants of “I HEAR MY HEART! BEAT!,” so it’s a relief to retreat to Holly’s restraint, although I note that the arrangement more or less “invents” The Shadows (Holly was an early and fervent exponent of the Fender Stratocaster) and the rhetorical role played by Allison’s cowbell at both the intro and outro.

Aside from these, “Listen To Me” is extraordinary in its effortless elisions from harsh to soft, and back again; the curiously over-exaggerated vocal drops of “LIS-TEN-TO-ME-HEE” pretty much writing the template for Merseybeat before dropping back to a honeyed, spoken whisper from Holly: “Listen, listen, listen to me,” to be followed by an excitable lead guitar and, again, a subtly disorientated vocal. If “Think It Over” might have been designed as Holly’s “Jerry Lee Lewis record,” complete with a rattling barrelhouse piano solo, then its implications are wider: Holly, again, teases his would-be Other as much as pleading with her, at one point asking, “Are you sure I’m not the one?” and then intoning “A lonely heart grows cold and old” (it’s the pause in the music that makes you remember the line).

Sides one and two are essentially split between Buddy and Crickets and Buddy post-Crickets (and even post-Buddy) but side two still has “It’s So Easy” with its vocal grunts suggesting that actually it’s very difficult, offset by some strange verbal throwaways (“Gosh darn that love,” “doggone easy”), the supreme “Rave On” with its introductory six-syllable “Well” and a propulsion so powerful that it could almost have been made by machines (and hence it is a natural precursor to rave music, as such); everything here has been accomplished, and works – and the unworldly “Well….All Right” which more or less spells out what McCartney is going to do with the Beatles but also moves with great naturalism between two different dynamic angles (moderately intense, and slightly more intense) with a rhythm that could properly be described as proto-reggae, and some long-form cymbal work from Allison that almost breaks the boundaries of tempo and reminds us not only of Billy Higgins’ cymbal work on Coleman’s “Lonely Woman” but also looks forward to Tony Williams on things like Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage”; drifting and patient.

The rest of the record concerns itself with what Holly did, or would have done, next. “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” the first posthumous UK number one single, was easily his biggest hit here, but although Adam Faith and John Barry would forge entire careers out of its vocals and semi-pizzicato string arrangements (before discovering something of and in themselves in the process and mutating into something different), it does not really convince, partly because its author, Paul Anka, seems to have written the song as a sort of Holly pastiche; so although the singer makes with his “Golly gee”s and “Whoops-a-daisy”s, he comes across as slightly forced, and in attempting to turn him into an adult – or make him grow up – he uncovers levels of accusatory bitterness which had not really been present in his previous work (significantly, he sings nearly all of the song in his lower register). Dick Jacobs’ cheesy arrangements also do Holly no favours on “Raining In My Heart,” a good song and a concentrated vocal ruined by overblown, sound-effect strings, or on “True Love Ways” which, although showing some advance from “Not Fade Away” in its haiku-like lyrical structure (“Just you know why/Why you and I”), is marred by corny Palais dancehall tenor saxophone and piano. If Petty really wanted to turn Holly into a prototype Bobby (he needn’t have bothered; Bobby Vee, who took over and performed the gig Holly would have played had his ‘plane made it, profited almost immediately as a sort of Holly-lite substitute, even going so far as to cut some sides with the Crickets in the early sixties; one album, Bobby Vee Meets The Crickets, narrowly missed the number one slot here in late 1962) I doubt he would have got very far; Holly was a little too animated, insufficiently sedate, for this sort of thing to work effectively.

Much better are the four concluding tracks: “Peggy Sue Got Married,” originally cut with the Crickets but here done with a revamped instrumental backing track, is one of Holly’s last great songs, and one which suggested he already knew that one kind of game was up; throughout the song he is extremely reluctant to tell the listener what has happened, endlessly putting it off or making excuses, but finally – it’s not gospel, folks, but I heard it, so who knows – he reluctantly divulges the titular information, except that he remarks “You recall that girl that’s been in nearly every song” and you realise that actually she only unambiguously appears in one other song, except that all these songs might be about the same, unattainable woman, or idealisation of a woman – Holly as Lubbock’s own Robert Graves, with Peggy Sue his own White Goddess? – and Holly’s guitar solo is appropriately melancholy, clearing the path for George Harrison. “Bo Diddley” is a very decent attempt to expand on, or refract, the “Not Fade Away” template, and Holly clearly has a good time with his ebullient vocal, even attempting an impression of the great man himself in the last line. His “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” with its ukulele-style lead guitar, is more than worthy of comparison with Chuck Berry’s original (which latter is pretty unequivocally a prototype black power anthem). And “Wishing,” which climbed our charts as the Beatles were settling in, is a fitting farewell, handing the baton over, with its foretelling echoes of both Beatles and Shadows, and Tommy Allsup’s extraordinary lead guitar; his run behind Holly’s vocal in the second middle eight recalls nothing so much as Nigerian hi-life music.

So where could Holly have gone? There is of course the example of his near-contemporary from Texas, whose career rose after Holly’s passing; Roy Orbison, who in his own way highlighted what might be described as the darker side of Holly’s muse – not that Holly would have gone in for doomed operatic wailings, but things not represented on this album (“Because I Love You,” “Love’s Made A Fool Of You”) do suggest a shade to the prevalent lightness. Or there is another Texan, born in 1936 – Kris Kristofferson, whose career echoes what might have happened if Holly had become more involved in the country scene, as seemed to be on the cards, and made his subsequent reputation as a songwriter and producer. He might even have discovered and nurtured fellow Texan Janis Joplin, but it would be naïve to think that Peggy Sue could evolve into “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands”; as “Peggy Sue Got Married” makes clear, she is now in the world, in the air we communally breathe; Peggy Sue is all around us, maybe even part of us. Still, his death appeared to mark a slow sea change in how pop music was approached and performed; if he was a bridge leading from the original rock ‘n’ roll pioneers, then he could hardly have expected to lead to Fabian or Bobby Rydell. The death of Ian Curtis, though coming from an entirely different, and probably opposite (or opposing), perspective, would have a similar effect on progressive British pop in the eighties. But if you have to look for evidence of Holly, look around you, on every Beatles album up to and including Let It Be, on most Dylan, and even unto “Gangnam Style” where similarly besotted tricks with language, intention and implications are perpetuated to prove an unexpected late bookend to “Peggy Sue,” proving that The X-Factor has not closed off all pop avenues for (anyone’s) good.